It’s a familiar refrain, but the world’s oceans and its ecosystems remain largely unknown and unmapped by mankind. According to scientific estimates, 91% of ocean species have yet to be classified and at the current rate of progress it would take several millennia to achieve knowledge comparable with our current understanding of the Amazon rain forests.

But while it might take some time to redress that balance, the audacious and multi-faceted vision of a UK-based startup to, in its own words, ‘make humans aquatic’ could herald the beginnings of a change. DEEP, an ocean exploration and technology company, recently emerged from two and a half years in stealth mode to unveil its bold plans to establish a permanent human presence on the ocean floor by 2027.

“We are here to revolutionise the way that humanity interacts, accesses and ultimately understands the ocean,” declared Sean Wolpert, DEEP’s president for the Americas during the company’s press launch at its headquarters in Avonmouth, north of Bristol, in September. Grandiloquent perhaps, but the urgency to better understand the ocean’s importance to the climate cycle is self-evident. Moreover, Wolpert notes that the untapped potential of these marine ecosystems – the complex chemical processes that sustain them – represent huge opportunities in areas such as biomedical research.

It’s been argued that we know more about deep space than our own ocean depths, but the two fields of exploration are growing increasingly intertwined, particularly as efforts to send manned missions to the Moon, Mars and beyond gather momentum. For more than 20 years, NASA’s NEEMO [Extreme Environment Mission Operations] project has been sending astronauts, engineers and scientists to its Aquarius underwater facility off Key Largo, Florida, for simulation exercises. However, its operating depth of 19 metres pales in significance compared with DEEP’s ambitions.

The Sentinel system

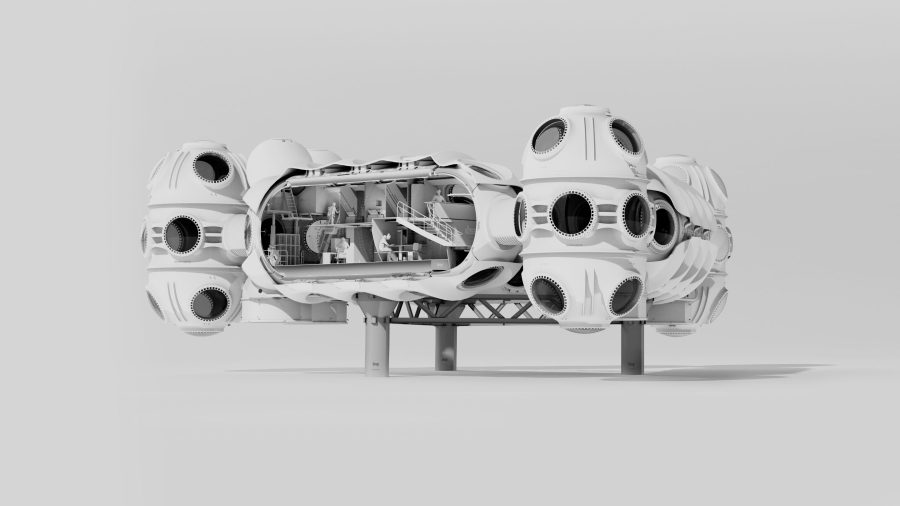

At the heart of DEEP’s vision is the Sentinel, a modular underwater habitat that will enable scientists to live at depths of 200 metres for 28 days at a time. The Sentinel system is designed to be redeployable, habitable for long periods and surface independent. Working closely with class society DNV, which has granted the design Approval in Principle, the technology has been developed without compromise to safety.

Each cylindrical module is six metres in diameter – roughly the diameter of a Boeing 777 fuselage – and could accommodate a standard crew of six, allowing for a high tempo of diving operations and other research, however by combining and reconfiguring the modules infinitely largely operations would be possible. Vertically assembled modules could serve as nodes for a multinational research station.

Interior detail diagram of the Sentinel. Source: DEEP

The Sentinel system has been designed with deep-sea research in mind, facilitating scientific research over extended periods. Source: DEEP

As Steve Etheron, DEEP’s president for EMEA, points out the idea of subsea habitation isn’t completely new and the Sentinel’s design journey began with an investigation of everything that went on in the past.

He comments: “The 60’s, 70’s and early 80’s were a period of immense innovation in subsea habitats, but then it went quiet for a few decades. We started by going through all the papers and research from that period and pulling together the best lessons that we could and developing a set of principles.

“We learnt a lot from how people have worked on the International Space Station and how people have worked on space habitats. So [with the Sentinel system] you can install scientific equipment and everything inside interacts. Anything that is inside can be taken out through the moon pool, making it possible to change in situ and re-task the system.”

One important consideration is the Sentinel’s ability to operate autonomously. “It’s very tempting in building this to assume you have a huge research vessel or support platform above you, which has often been the way of doing this in the past. The problem is that the surface support is more vulnerable to bad weather than the habitat on the seafloor. It’s also extremely expensive, making the whole operation prohibitive from a cost perspective.”

Another of the central design tenets is re-deployability. Although each module would be solidly attached to a triangular base with foundations on the ocean bed, it can be detached with relative ease and relocated according to need.

But perhaps the most significant thing about the Sentinel, and the reason for the long period of secrecy, is that the project has already evolved far beyond concept renderings. DEEP’s Avonmouth facility is a veritable hub of industry, with an array of manufacturing equipment, testing facilities, and wave and test tanks in constant operation.

At the time of visiting, a veritable army of robotic welding arms had just been delivered which, according to Wolpert, will eventually constitute one of the largest and most unique arrangements of such equipment anywhere in the world. Wire arc additive manufacturing and generative design approaches are being used to ensure DEEP’s processes are supply chain resilient and energy efficient. Elsewhere at the facility a full-scale model of a Sentinel configuration is being used to scrutinise every aspect of the design’s habitability, right down to the choice of icons on the soap dispensers. It seems that nothing is being left to chance.

“We wanted to be confident we could make what we were talking about,” says Etherton. “We’re now two and a half years into this design, with a team of more than 100 people, with the greatest concentration being around engineering and design, as well as incredibly experienced operators to have the real-world experience fed into what we’re building. We have already [accumulated] more than 70,000 hours of specific engineering time.”

Submarines

To facilitate transfer of crew to the Sentinels, DEEP is also developing a complementary line of submarines designed with the same philosophy.

“We’ve [done this] by taking a step back and surveying existing interactions with submarines and submersibles. We need to elevate the reliability and accessibility of submersibles, increasing the amount of time that they’re in the water, not waiting to be repaired or sitting on a ship. We want to create the demand framework and demand models that allow those submarines and submersibles to be accessible, but also to ensure that the maintenance can be conducted by people with basic engineering common sense,” says Wolpert.

“You can achieve that with the modularity and standardisation of different components. That creates a wider range of submarines and submersibles that are able to address the many different areas and envelopes within the ocean. That also starts to bring down cost.”

However, DEEP is mindful that, while its resources are clearly plentiful (the company is a little coy with regard to where exactly its financing comes from) it won’t be able to achieve this without collaboration. Shared ownership models are being explored for both Sentinels and submersibles, while the company also plans to make the Sentinel docking process open source, allowing sub-manufacturers to participate within the ecosystem.

Another important consideration, one that DEEP is also investing massive resources into, is training. Last year the company acquired the former National Diving and Activity Centre, a converted limestone quarry in Chepstow, Wales, with waters of 80 metres depth that had previously served as a scuba diving facility. Although currently resembling a building site this will form the base for the DEEP Campus, with a syllabus encompassing not only training for divers and equipment operators but also with the aim of educating the wider public about scientific and environmental issues.

DEEP sees its mission as a scientific and environmental one, envisaging collaboration with educational bodies and media companies interested in deep-sea filming. One option it vehemently rejects is allowing its technology to be used for military or marine exploitation purposes, such as offshore mining. “We’re looking to partner with individuals and groups aligned with our mission of understanding and conserving the ocean. This will be contained in terms of the provision and capacity to sell [the equipment] on as there will be restrictions within that.”