Having gone through its first, exciting growth spurt, the US offshore wind sector has hit its next step – the ‘challenge phase’, we could maybe call it – where the country’s ambitions for clean, renewable energy come up against harsh market realities.

For example, the second half of 2023 saw delays hit some of the leading American offshore wind projects. In August, Vineyard Wind, developer of the US’ first commercial-scale offshore wind farm, announced that it was delaying its project off Massachusetts by a year, citing permit delays and supply chain disruptions. This was followed, in October, by Ørsted’s decision to halt development of its Ocean Wind 1 and 2 projects – a move blamed, again, on supply chain delays.

Last year also saw the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) warn that project delays could railroad the state’s attempt to establish 9GW of offshore wind power in its waters by 2035, while increasing the cost of such projects – with the ratepayer picking up the bill. Naturally, there are concerns that these delays could sap investor confidence in this burgeoning sector.

However, some builders remain stoic when assessing these developments. As Jim Cutts, CTV programme director at St Johns Shipbuilding, Florida, put it in a podcast with class society Bureau Veritas: “It’d be easy to assume that this new industry’s about to falter, but there are actually many other projects that are still ongoing. The US offshore wind industry is definitely here to stay.”

After its acquisition by Americraft Marine in summer 2022, the St Johns yard expanded its facilities, specifically to boost production of CTVs and other offshore wind support ships. “[We] recognised very early on that there had to be some level of real commitment to meet the challenges of the shortfall of suitable Jones Act-compliant vessels to meet US offshore wind industry requirements,” says Cutts. “While the yard is too small to build SOVs or other large vessels, the actual CTV size was right in our wheelhouse.”

Equipped with an 850tonne dry dock, a crane capacity of 500tonnes and a waterfront spanning more than 730m, St Johns has traditionally specialised in steel vessel construction, with some limited aluminium experience. This is about to change: as a result of the site overhaul, the yard has added undercover facilities to permit year-round aluminium boatbuilding. “We’ve gone from being able to build three vessels to something like eight vessels a year,” Cutts adds.

This increased boatbuilding capacity is a crucial feature, given the expected increase in demand for these CTVs, and especially when set against another serious challenge: a dearth of qualified manpower. “These lightweight, thin-skinned, heavy-duty workboats are somewhat new to the US,” Cutts continues. “With the large number of vessels required, all the [US] yards are competing for the same pool of skilled labour.” As a result, St Johns struggled to source enough qualified welders, for example, to meet overall demand, forcing the group to rely on subcontractors. “While more subcontract labour assists with the immediate requirements, it doesn’t add to the overall skillsets of St Johns,” he says.

As a result, the builder has set up its own onsite welding school, so that it can train up its workers to handle ongoing aluminium CTV production. “We even brought in a couple of British production experts, who have built many CTVs over in the UK, to advise on general construction practices, material preparation techniques and detailed welding approaches,” says Cutts.

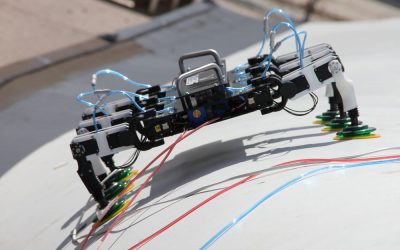

One of the WINDEA Offshore trio, pictured nearly ready for launch, at St Johns in Q4 2023 (image: St Johns Shipbuilding)

As former director of engineering at the now defunct UK builder CTruk Boats – one of the pioneers of offshore wind CTV development in the early-to-mid-2010s – Cutts believes that his experience in building UK and European crewboats to class rules grants St Johns a particular advantage when it comes to securing domestic US contracts for newbuilds.

He says: “We spent some time getting to know the design and engineering details, and discussing various construction methodology options, to understand the vessel configuration. Being able to discuss this directly with the naval architects – who I knew from before – did give St Johns a big advantage when talking to the customer.”

The yard has secured two domestic customers so far. St Johns is currently building three Incat Crowther-designed CTVs for WINDEA Offshore, originally intended to be chartered at the Vineyard Wind site, each featuring a length of 30m, a breadth of 10m, a draught of 1.4m and the capacity to carry 24 turbine technicians and six crew. Fashioned from marine-grade aluminium, each of the trio will run on four Volvo D13 main engines, rated a combined 2,060kW, for a service speed of 26knots and a top speed of 29knots. These WINDEA CTVs will be classed by Bureau Veritas (BV) and flagged by the US Coast Guard (USCG).

St Johns is also building a pair of 24m CTVs for Rhode Island-based operator Atlantic Wind Transfers, both of which are being produced to the specs of Chartwell Marine’s Ambitious class. This series includes dimensions of 23.9m x 8.7m, a 1.3m draught and a 24-technician capacity. These twins will be classed solely by the USCG.

While Cutts appears optimistic about the US offshore wind industry’s anticipated growth – and the increasing reliance on vessels to serve this market – he adds that most CTVs developed for the UK/European sectors are a good 10-12 years ahead of the curve, and that innovative US-built CTV designs may take a while to break through. “We already know that Europe and the UK have a well-established offshore wind industry, and there are many 10s, if not 100s, of CTVs in operation there,” he says. “Because of that, those operators have the confidence to be a little more adventurous in the vessel designs that they’re ordering. In Europe and the UK, we’re seeing hybrid propulsion systems being installed on [CTVs], and surface effect ship [SES]-types are being ordered as well” (see, for instance, Ship & Boat International May/June 2021, pages 18-22).

Cutts continues: “Whether the US market will get to that stage any time soon is debatable – but as the industry matures, and specific US operational conditions and challenges are better understood, we will see some level of vessel development. We may see CTV-type vessels staying offshore for longer periods: either operating as more capable daughter craft to the large walk-to-work or floatel-type vesels, or as larger CTVs with technicians’ accommodation actually on board.” While conceding that these developments “will definitely take some time,” Cutts optimistically concludes: “The standard CTV that we all know is definitely here for the long haul.”