The past few years have seen regulators warm to nuclear power’s potential, but a major challenge remains: persuading investors to fund nuclear-powered commercial ships.

This was the main theme of the roundtable Is Nuclear the Missing Piece in Maritime Decarbonisation?, hosted by classification society IRClass during London International Shipping Week in September. Gihan Ismail, director of shipping fund/asset manager and vessel operator Marine Capital, told delegates: “From a technical perspective, I’m sure we will get there, and it will probably not take decades. But the commercial viability of [nuclear] technology will take a lot longer. IMO has still to develop a comprehensive regulatory framework for nuclear ships, and this will take time.”

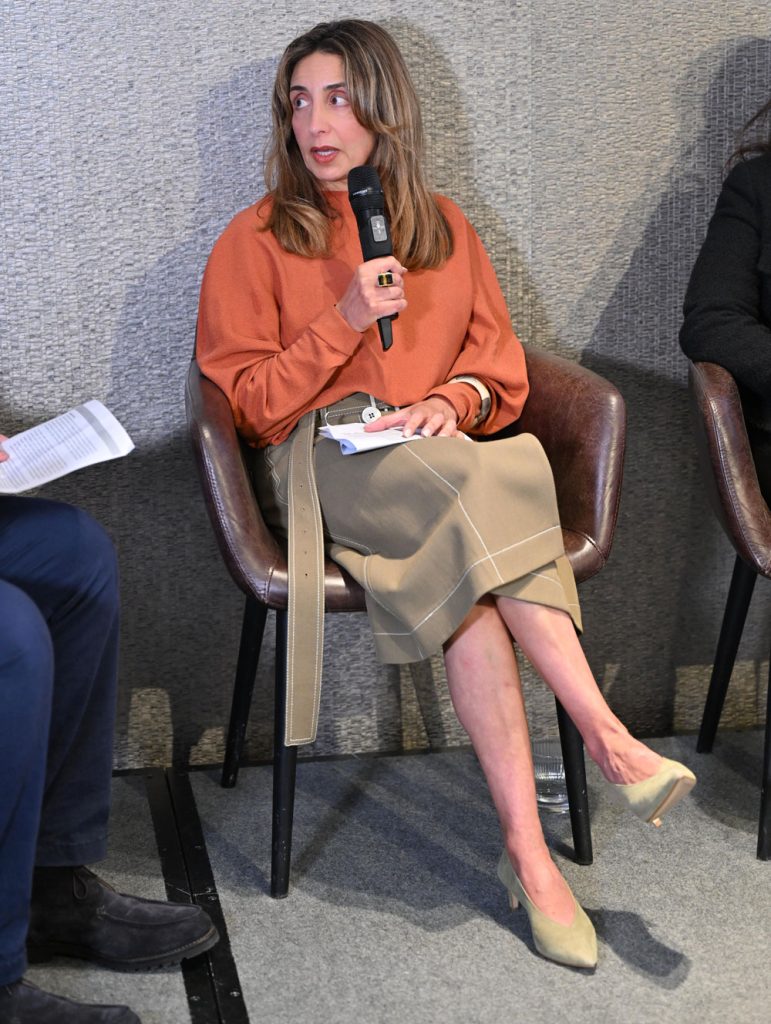

Part of the problem, Ismail emphasised, is that “shipping and nuclear are two areas where institutional investors are very reluctant to invest directly”. She continued: “As maritime insiders, we know the risks in our industry and how to manage them – but a financial investor who has no familiarity with our sector just sees, for example, Ever Given stuck in the Suez Canal. As a result, [investors] tend to ascribe a higher risk premium to shipping.

“Institutional investors are reluctant to invest in shipping because they don’t like the construction risk, or the ‘first of a kind’ technology risk, or the long lead times, because there’s then uncertainty over capital deployment and the risk return model. They are also unwilling to invest in nuclear, partly because nuclear energy development is complex and has pretty much always been tied to national security. The project lead time is very lengthy – typically 16 years from regulatory approval to construction – and it’s typically beset by significant cost overruns and delays.”

Ismail expanded: “[Investors] have an investment period in mind, which is not infinite, so the funds will often have a fund life of, say, seven to 12 years – and you can’t really invest in a project where you’re not getting to see any income or return come through until after your fund life. These things need to be overcome if we’re going to see investment in commercial nuclear vessels. Investors want to see that this works in a commercial setting; they won’t want to take any kind of operational risk where there is no commercial track record.”

Gihan Ismail, Marine Capital: “Investors must be convinced that nuclear energy actually is ‘green’… I think there’s been a great deal of ambiguity”

Anouskha Bachraz, director, transportation advisory at multinational banking and financial services company Société Générale, commented: “Banks are conservative – there’s always a little bit of apprehension when you’re transitioning to new fuels. Even when you’re trying to finance LNG or methanol, banks will raise questions like: ‘How will it work? How will you find the methanol? Where are the green corridors?’ Banking is probably going to be one of the last sectors to support nuclear being used on commercial vessels.”

Given the high costs of producing a commercial nuclear ship, adopting a leasing model for onboard small modular reactors (SMRs) could spread the upfront costs of nuclear technology over time, enabling smaller operators to adopt these reactors without massive capital investment. As Bachraz pointed out: “Right now, SMRs are expected to have a lifespan of 40-60 years, which is much longer than that of your average ship” – and their compact, modular nature means they could suit various vessel types, making it possible for one reactor to fuel a small yacht, a bulk carrier and a landing vessel in its lifespan, for example.

One concept with the potential to lure investors – and one that has become increasingly popular in recent years – is that of green shipping corridors. With more than 60 such corridors established worldwide, and more on the way, they seem to be a burgeoning trend. However, Ismail warned, relatively few of these corridors are operational. “These take a long time to set up because of all the additional stakeholders involved,” she said. “You’ve got the shipowners, the operators, the ports, the charterers, the banks and other financing entities…and they all have to come together and agree to bear the cost together. The very few [green corridors] that are operational are operational because there’s been some kind of government support that has underwritten some aspect of that which has enabled those parties to take those risks, bear that extra capex and have some kind of certainty that that capex is worth it.

“You’ve got to have charterers who are willing to enter into duration. It’s not as simple as two countries or two ports getting together to enable that.”

‘Is Nuclear the Missing Piece in Maritime Decarbonisation?’ was hosted by IRClass during London International Shipping Week

Inevitably, the discussion led to the public perception of nuclear energy, and how this alt-fuel’s pariah status may be scaring off investors. It’s easy to understand why nuclear power advocates become frustrated; nobody seems to be as concerned with, say, ammonia, which can cause blindness, severe burns, lung damage and explosions in an accident, and devastate aquatic ecosystems in the event of a spill. Then again, the public hasn’t been subjected to decades of books, movies, documentaries and songs about the horrors of ammonia.

Ismail said: “Nuclear is still regarded with a good deal of suspicion. Investors must be convinced that nuclear energy actually is ‘green’, and I think there’s been a great deal of ambiguity. For example, the EU has only included nuclear as a ‘transitional’ energy in its sustainable finance directive taxonomy in 2022, and the UK government doesn’t actually include nuclear in its green finance framework – although the Climate Bonds Initiative [CBI] accepts that nuclear does align with green principles – so you need to convince investors that they are actually investing in a green energy source.”

One driver of change might be the adoption of SMRs by ‘Big Tech’, Bachraz noted. “Amazon, Microsoft and Google all need higher levels of energy intensity to be able to power the data centres they need for AI,” she said. This could break the ice with some previously reluctant investors; Bachraz added that some banks are already showing interest in the feasibility of financing these data centre SMRs on an ongoing basis. “Once you have a framework for financing SMRs on land, you can develop a framework on the shipping side,” she said.

Which brought the panel to the point: can the shipping industry obtain the financing it needs to pull this off without government assistance? In Ismail’s opinion, it’s inescapable that government has “a very big role to play – not just in nuclear, but in the whole energy transition, because a lot of commercial hurdles are not going to be solved solely by the private sector or the commercial sector”. She continued: “We all know that the cost is huge, so government can’t fund it alone – but there are just certain risks the private sector will not take, or will be very unwilling to take. It’s not just the banks that are conservative – it’s also institutional equity investors.”

For the full, in-depth report, see the October 2025 issue of The Naval Architect