The global expedition cruise fleet continues to grow at a brisk pace and at the high end of the market the cruise yachts that some hotel groups are introducing mark further diversification of the cruise industry. The switch to clean fuels poses challenges for both, but these are felt more in the expedition segment.

Both of these ship types are much smaller than most of the mainstream cruise vessels – even in the luxury segment of this, few newbuildings are less than 50,000gt. However, the off-the-beaten-track nature of expedition cruising and the exclusive luxury character of cruise yachts means that in both cases the ships should not be very big, or at least not accommodate large numbers of passengers.

The cruise industry’s need to decarbonise is placing owners of both types of ships in front of a challenge as CO2-free fuels take up far more space than oil.

The Ritz Carlton group, which recently took delivery of the first of its 25,400gt cruise yacht newbuildings, called Evrima, decided to use LNG, the cleanest fossil fuel, on its second class of ships: the gross tonnage increased to 46,750 and capacity to 456 passengers from 298 on the first ship. Space ratio – gross tonnage divided by passenger capacity – will increase to 102.5 from an already high 85.2, indicating that the larger ships will also have more space per passenger.

Cruise yachts like those of Ritz Carlton or Four Seasons will focus on smaller ports than mainstream cruise ships, but unlike expedition vessels, they do not sail in the most remote regions of the world, such as Antarctic.

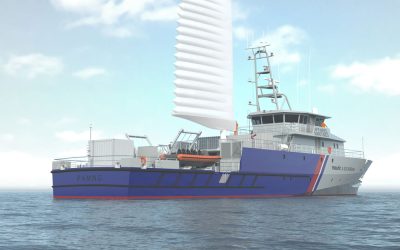

Expedition cruise ships frequently operate in regions where distances between places where you can bunker can be very long, notes Anders Ørgaard, chief commercial officer at OSK-Ship Tech in Denmark. Hydrogen is often mentioned as a potential future green fuel for passenger ships, but OSK-Ship Tech has carried out a study to find out how it would suit as fuel of the expedition cruise ship fleet currently in service. The result was that none of the existing ships of this type would are able to accommodate hydrogen fuel onboard.

“Fuels like hydrogen cannot be stored in square tanks in the double bottom as is the case with oil, instead it has to be kept in circular tanks above the double bottom. This alone affects the design of spaces in the hull. Together with the fact that it takes up far more space than oil, the outcome is that payload and passenger spaces will also be affected,” Ørgaard says, adding that methanol could be a more viable option for these vessels in the future.

Space and availability critical in expedition segment

For the expedition sector, the space onboard is one challenge and the availability of clean fuels in various parts of the world is at least as significant. There is no green fuel available at the moment that would suit the needs of SunStone Ships, the Miami-based provider of expedition cruise tonnage, says Niels- Erik Lund, the company’s CEO. The company currently owns 12 vessels ranging from about 4,000gt to 13,000gt and it is working on an order for newbuildings of about 12,000gt.

Lund points out that some ships in the expedition sector are quite a bit larger – of up to some 30,000gt – but these operate in the very top end of the market. Many operators of expedition cruises, including those that charter tonnage from SunStone Ships, are in a different segment and operate smaller ships and Lund says he expects this situation to remain.

“LNG takes up seven times as much space onboard as MGO,” Lund points out, adding that the company’s ships need to operate cruises of 24 days in duration and make a voyage from Ushuaia, Argentina, to Svalbard, Norway, without passengers to go from one charter to another: the distance is roughly 11,000 miles.

These factors make two points clear. Firstly, it would be completely impossible to fit tanks big enough to hold any other fuel than MGO on the size of ships that the customers of SunStone Ships need and secondly, as expedition cruises visit some of the most remote parts of the world – north and south, east and west – no other fuel would be available in each port where it would be needed.

However, Lund sees a way for the expedition cruise industry. The first step is to improve the cleanliness of MGO by developing the existing technologies. The second step can be the installation of fuel cells that could partially replace diesel gensets.

“We have looked at the possibility to replace four gensets by a combination of two gensets and two sets of fuel cells,” he tells The Naval Architect. While this step could be taken in the fairly close future, replacing diesel power entirely by fuel cells will still take time.

Nuclear power could also offer a way forward as molten salt reactors are now emerging as a potential candidate for the maritime sector. These offer much lower risks than pressurised water reactors that are used in power generation ashore and in naval vessels, Lund notes. “But this will probably be 20 years in the future,” he adds.

The choice of an emission-free fuel on ships operating e.g. in Arctic and Antarctic waters can happen in two ways: firstly, the shipping industry can voluntarily opt for a certain choice or secondly, the regulators can impose their decision on the industry, summarises Vesa Marttinen, senior advisor at the Finnish consultancy MarineCycles.

“In practice, it is likely that some fuel option will be favoured in the decision making, because it is difficult to be technology neutral. A lot will depend on how CLIA (Cruise Lines International Association) and the cruise industry as a whole can work with IMO and regional regulators,” he explains to The Naval Architect.

Rethink what matters in environmental footprint

All the new CO2-free fuels will take up significantly more space onboard than oil and as expedition cruise ships need to have a long range, it is difficult to provide enough bunker capacity on what are small vessels in comparison to the mega ships employed mainly in the contemporary market segment of the mainstream cruise industry.

On the other hand, ships are only allowed to land 250 people on Antarctica at a time, which significantly limits the size of the expedition cruise vessels.

“Perhaps we could think if the size of the ship really is a relevant way to assess the environmental impact of a cruise in these waters,” Marttinen continues. He suggests that if only 250 people could be allowed to land per day, a ship with 500 passengers could operate in the region simply by allowing only half of them to go ashore each day. This would open the door for the construction of larger vessels with more room for green fuels.

In this case, the environmental impact could be measured by benchmarking all aspects of the cruise per passenger, building an index of them and then using this as “equivalent environmental impact”. This could already be used today, helping operators to measure and reduce their footprint, while in the future it could allow bigger ships that can use green fuels to the region, Marttinen concludes.