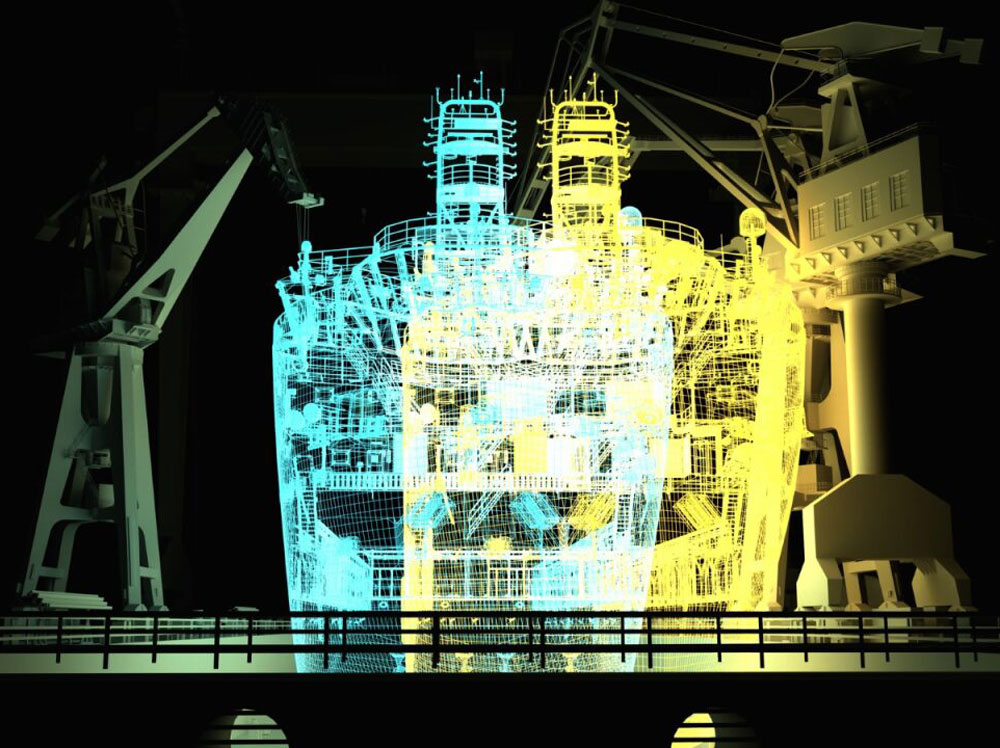

CAD/CAM solutions and digital twin technology, by their very nature, overlap – and this could yield excellent benefits for naval architects, shipbuilders and the owners and operators of new and existing vessels. CAD enables users to create detailed digital designs, and CAM allows them to automate production, making it easier to build complex ships (and offshore platforms) accurately. Digital twins serve as virtual representations of real-world objects, enabling users to monitor, test and tweak them in real time.

As Craig Tulk, product business analyst at CAD/CAM solutions developer SSI, puts it: “A CAD model, whether it contains 2D or 3D info, is a form of a digital twin.” This perspective highlights the foundational connection between CAD models and digital twins but also raises questions about how much detail—or “DNA”—a CAD model needs to qualify as a digital twin. “The question is, what parts of the DNA does it actually need to carry to suit its purpose?” Tulk tells The Naval Architect. “A production-based CAD model design may carry a whole lot of DNA but might not break it down into all of the fine details you might require for a maintenance-based digital twin.

“For example, it would give you details about what engine model/version fits into a particular space and what connects up to it, but it wouldn’t provide specific details about fuel injectors or turbo charger breakdown details in a way that would be specifically useful to anyone who wants to service those engine parts later in the vessel’s life. Yet, it can provide a faster path for them to get to that information through a linked digital thread from that engine model/version that was installed.

“It really depends on the purpose of what you’re using the digital twin for. At the detail design and production stage, it may not be considered worth the money to spend adding details about where every onboard sensor will be located. Similarly, the ship operator may want these sensor details for operational monitoring, but doesn’t need to know how the ships’ block units were assembled.”

Tulk highlights that “we’re seeing a metamorphosis in our industry”, in which clients are extending the traditional use of CAD/CAM as a ship design tool to also cover post-delivery monitoring and maintenance. “CAD/CAM is usually used for production design, which is where the costs are incurred – the cost of building a vessel is about 90% greater than the cost of designing it,” he says. “In turn, the cost of operating the vessel can well exceed the costs of designing and building it, so customers now want to manage and maintain that digital thread from the earliest design stages right through to the operation of the vessel.”

Additionally, using CAD/CAM data to create a digital twin of the vessel is proving beneficial for personnel training, especially in the naval and patrol vessel segments. “The digital twin shows all the compartments of the vessel and what they are purposed for: for example, where fire stations and life rafts are located on the ship,” Tulk says, “so trainers can use that 3D model as a virtual representation for training purposes alone.”

One recent trend is reusing early conceptual and preliminary design data, such as 3D hullforms, to streamline production of similar vessels. “Traditionally, each ship’s design started from scratch – conceptual, preliminary, contractual, then functional and production stages,” Tulk explains. “Now, designers can reuse digital assets from early stages, saving time and costs.” Another trend is hosting CAD/CAM models and digital twins on the cloud, which, Tulk notes, was “unthinkable a decade ago” due to technological limits. Cloud solutions enable real-time collaboration and data access, which in turn permit effective lifecycle management of the asset via the digital twin.

Tulk also highlights finite element analysis (FEA) and component traceability as emerging CAD/CAM and digital twin tech trends. FEA, now fully digital, allows designers to carry strength calculations from early conceptual and preliminary design phases—where hull shape and strength are defined—through to the final build, to help ensure the ship meets its initial performance and safety goals. Additionally, the digital thread can be used to help owners/operators to trace designed parts to their physical counterparts. So, should a plate fail to meet specifications, users can more easily trace it back to its source batch, identifying other potentially faulty components. “People can ask: ‘This piece of steel came from this bad batch of plates—but what else that’s on board came from it?”, says Tulk. “It’s a faster, easier way to verify that what was factored into the design is fit for purpose and is safe.”

For the full article, see the August 2025 issue of The Naval Architect